It turns out that so does everyone else:

I could come up with a comprehensive list of organizations to suit your school-building desires, but that would be an exercise in frustration and wasted internet credit. My favourite, though is this group. They built one kindergarten in the Volta Region of Ghana with carefully selected textiles and a unique, modern design that aims to “raise the bar on the designs of kindergarten facilities in Ghana…”. The whole thing only took one month to complete and even used locally-sourced management (from Accra) and materials. Success! Now, let’s start an organization and feel good about ourselves help children to have better futures in Africa.

Because, obviously African children don’t have bright futures due to the lack of physical structures required for schooling, right? I mean, what else could possibly prevent them from getting an education and being successful later in life?

In fact, for the past four years enrolment in Junior High School has increased steadily in the Northern Region (NR) in Ghana. On average, the increase has been about 8000 new students each year (R = 0.97).

So we definitely need to build new schools. Quick, call your friends and family, rally your school, call the textiles designer! We’ve got 8000 new students to prepare for and only a short time before they’ll be starting school. Thankfully we can whip up a state-of-the art, bar-raising school in only one month. If we get 53 teams organized across the country, we can singlehandedly ensure that all those new students will have schools for the next school year. And who knows how many future-changing NGOs we can get out of the operation!

Hold up.

It also turns out that the picture is a little more complicated than that.

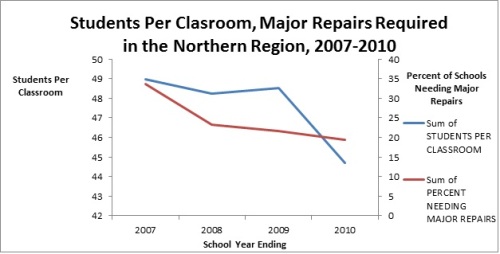

The increase in enrolment in Junior High School (JHS) in the area has been far outpaced by the rate at which schools have been built and as a result, the ratio of students per classroom has been decreasing by 1.3 students each year (R = 0.82) since 2007. Additionally, the percentage of schools requiring major repairs has decreased by about 4.5% each year over the last four years (R = 0.91).

Fewf. Looks like all of the do-gooding that schoolbuilders have been up to has paid off. There’s no need to worry about those 8000 new students not having classrooms, since the amazing work they’ve done is already going at the pace it needs to in order to keep up with demand. Just continue with what you’re doing now, schoolbuilders, and Northern Ghana will be fine.

Actually, it seems as though construction of most of the 132 new JHSs in the NR in the past four years was managed by district offices with the help of School Management Committees (SMCs). And Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs) raised most of the money for the major repairs required by existing schools.

But surely all of the schoolbuilding my Western colleagues have been up to has had some impact on education in the NR. To be honest, though, I don’t know what that impact has been and neither does the REO here. That’s because almost none of the wonderful schoolbuilders offering their services to Ghana talk to the Ghanaian government about their activities. When they do, the details are vague, incomplete, or incorrect. As a result, coordination of external activities by district offices is very, very challenging.

No matter, though. Those courageous schoolbuilders are doing their darnedest to tackle the biggest issue facing education right now! What’s the problem with a small lack of reporting, when the work they’re doing is so paramount to giving Ghanaian children bright futures?

Well, maybe access isn’t really the biggest issue. Gross Enrolment Rate (GER) is a measure of enrolment normalized to the population. In the NR, the GER currently sits at 70%. It is up by 10% since 2007. So, access to education is increasing and families are taking advantage of that increase.

Now, keep in mind that these numbers are based on census data that is ten years old with a 2.7% yearly projected population increase.

Take a look at this, though:

The Basic Education Certificate Exam (BECE) is a standardized test for all of West Africa that tests JHS students’ basic ability in Maths, English, and Integrated Science. If a student doesn’t pass the BECE, s/he will not go to Senior High School (SHS) and will not be eligible for university. Do not pass BECE, do not pass GO, do not collect $200.

For the last four years, there has been little change in the BECE pass rate in the NR. The boys sit at an average of 47% passing and the girls sit at about 33% passing. That averages out to a pass rate of about 40% over the last four years and translates to about 51 000 students (29 000 boys, 22 000 girls) who have not had the opportunity to go to SHS. For those 51 000 students, JHS3 is the exit point from education for the rest of their lives. Talk about a leaky pipeline.

Imagine going into an exam with 9 of your classmates. You’ve studied hard, despite setbacks, and feel as ready as your teacher could make you feel (which is likely not all that ready—more on teachers in a later post). Unfortunately, only 4 of you will even pass that exam and none of you will really do well on it. The other 6 of you will lack the skills required to do anything productive with your basic education. In fact, it’s likely that those 6 are illiterate. Now consider that not only can you not read at age 15, but also that you’ve just wasted 9 years of your life learning things that cannot be useful to you in the future, when you could have been perfecting your maize growing skills and adding to your family’s livelihood.

But, hey, at least you had a school in which to do it. And the textiles were so nice for all of those 9 years.

-C

THANK YOU CHRIS.

Thank you. Thank you for giving me a fantastic, stats-supported, pre-analyzed, field-based statement I can send to teachers and fellow do-gooders to help explain to them why plonking a building in the middle of the Guinea Savannah, while highly cathartic to disconnected white people, doesn’t actually even begin to address education.

I’m looking forward to your weigh-in on teachers. And when you get back the Canada, the YE team owes you a beer and a long talk. And that will probably turn out to be me, so prepare.

Keep rocking it out there. I continue to be really impressed.

-Ash

Thank you for sharing the stats and the complexity of the issue but I honestly feel that your sarcasm and negativity detracted from the points that you made.

Yes the system is flawed and education isn’t as good as it should be, but don’t we have similar issues in Canada? Quebec has a 30% drop-out rate, no? And do you really feel that a bad education is better than NO education? That it is in fact useless for a farmer (or farmer’s wife) to go to school? Come on…

All projects have negative bits, and some more than others….But I do think your throwing stones technique is counter productive and lacks nuance….and humility.

I think you make good points and have important insights to share…REALLY important insights to share but I think they can be more clearly with less negative feelings to those individuals who, just like you, are trying to have impact.

Thanks for the feedback, Mary!

I’m not sure of the Canadian stats, but I hypothesize that some areas suffer as badly as those in the Northern Region of Ghana. Unfortunately, I don’t have the time or internet access to go and dig out those stats. I’m more interested in the process behind retrieving and analyzing them, anyway.

I don’t think it’s useless for anyone of any age to attempt an education. However, it’s useless for them to do so with the mindset that education = good life. In the NR, this is not necessarily so. Instead, getting an education is a lot like playing the lotto without knowing your odds, since these data are not freely available to the public as they should be according to Ghanaian policy. Even if they were, I’m sure they would not be well understood. So basic education ends up being a 9-year long risk. This is the same in Canada, but the major difference is that the data about the education-good life connection are readily available to those seeking out that education, so the risk involved is a lot more fair.

It’s true that all projects have good and bad aspects. I didn’t really highlight the good aspects of schoolbuilding, did I? They do exist. The Ghanaian government may have built the majority of those 132 schools, but guess who filled the gap? Do-gooding schoolbuilders, in fact. Also, even if the schools do not end up being used as schools, they serve as multipurpose infrastructure that could serve the communities in other ways. Finally, I think that engaging Westerners IS another benefit. Who knows how many students go to build a school and realize that maybe they can do a lot of good for development in other ways? I think that opening up the culture bubble of the West through these projects is definitely a good aspect. I have a friend whose life was changed when she built a school in an African country. Now, she’s a kick-ass EWBer. I can’t deny the potential for that kind of thing to happen.

I have to agree with you about this post lacking humility and nuance. Read my next post to find out why.

Hey Chris,

Thanks for some data on education in Ghana. Although, I’ll have to agree with Mary that perhaps your tone of messaging is a bit over the top, thank you for spending the time to analyse the really issues facing education in Ghana.

Every time I see a donor allocate money for school building projects, it kinda kills me inside because I know that 50% of the students that will attend that school will likely never see a teacher 3/5 days of the week. As to the debate on whether or not a bad education is worse than none, I really don’t know. All I know is that there are thousands of youth in Ghana who want to learn, who truly want to be educated but who are being shafted by a governmental and development partner system that undervalues quality. When somebody says they’re going to build 13 schools in District X, it literally means 13 school buildings. I don’t even consider them “schools” because a school is a system. It has teachers, chalk, chalk boards, care keepers, administration, students, physical infrastructure. Few donors and do-goo NGOs look beyond the physical infrastructure.

This is why the quality of education in Ghana is decreasing drastically. I would love to see a donor or NGO put money down to fix the problems associated with teacher motivation, or even just access to qualified teachers.

I’m reminded of a quote I heard from a highly educated, and respected Ghanaian within the government. “I’d rather sit outside under a tree with a good teacher, than sit inside a fancy building with no teacher.” What she is saying is that physical infrastructure is not the solution to Ghana’s education problems, in fact it’s only in the limelight today because of the Millennium Development Goal of universal primary education.

Westerners need to start questioning the motives of NGOs who are building schools overseas. Are they building systems, or building structures?

Mina

I definitely agree with Mary. You made some very harsh and serious accusations without mentioning any of the intangibles associated with going to school, the problems with standardized testing or the quality of teachers (although you did write a post on this previously)

The way I see it is that there are different routes that can be taken. Build one school, make it a good school, make all the teachers top of the line, have all the students there graduate continuously year after year and then move on to build another school.

Or build a lot of schools, then begin addressing the issue of education quality and teacher proficiency and the passing rate of the students.

There will be critics to both methods which is important because eventually there will be enough schools built that the focus must shift away from building them to making them of quality. It would seem that you are working on trying to figure out if there are enough schools now, that the focus must be shifted. Would you bash on the same organizations that built the schools if in a few years they change their motto to

“You helped build the school, now help staff it with the best teachers!”

Thanks for the feedback, Ryan! It’s always appreciated.

I’m not sure if I made any tangible accusations outside of the issue with NGOs not reporting their activities (and this is a serious issue that deserves an equally serious accusation, IMHO). In fact, if you read between the lines, you’ll find that I noted that the activities of schoolbuilders in the NR helped to fill the gap of building new schools last year.

I love your analysis of the two ways of approaching education access. It’s one that I’ve been working on myself in my work for the past little while, because I’ve seen that the current attitude is to attempt both methodologies at once. Both aspects (quality and access) need serious work, so the REO is working on them both at the same time. I’m trying to figure out how to get them to do a value-add analysis in order to decide if this approach is good, or if it needs work. Any thoughts on that?

I would criticize organizations like the ones you mentioned at the end for not doing so at the outset of their project, but I think it would be a refreshing attitude shift to see an organization do that. Unfortunately, right now there isn’t a single NGO in the NR working on quality or teacher distribution. It’s all access, access, access.

Thanks for the comment.

Hey Chris,

Thanks for the post – a quick suggestion: it looks like a lot of the graphs you’ve attached won’t load. I’ve tried it on different browsers here with no luck. The two that won’t load are the second two – the resulting error says the file is missing.

Any ways, on to the post! With the situation you have described it sounds like there’s a major ‘category mistake’ in the minds of thee school builders. Ryle, who wrote on the subject, outlined an similar situation in one of his books. A foreign student comes and visits a country and after waling around a campus all day says something to the effect of “this is all nice, but where is the university?” – rather than seeing the university as a collection of people, ideas, processes, and buildings, the student was looking for one physical building. Rather than see schools as an education provider made up of people, materials, and four walls, it sounds like the projects you have outlined only look at the four-wall component. If this notion is true, how do you think NGOs, like EWB for example, can do a better job breaking down this notion?

A few questions –

With the amount of kids in Calgary who raise money for schools in “Africa” alone, it seems like the trend of more and more schools being built with good intentions won’t buckle. How do you think countries like Ghana can better leverage these good intentions to achieve better education outcomes?

I had a feeling from your post that you feel the vast majority of projects involving school development have it wrong – have you considered digging a little bit deeper into the actual programs organizations run?

I met some school builders in Zambia who make a concious effort to ensure that well trained teachers are both hired and have a sustained income string before lifting a single shovel. But what gets this organization their money? Talking about buildings and offering well-to-do white people a chance to come build. I am not saying it’s good or bad, but I feel there is more nuance to the situation than may be apparent at first glance.

On the test pass rates – I am wondering if the way the data has been treated may lead to aggregation bias? For example, aggregating the whole region may create a geographic bias, and looking at only four years may create a temporal bias. What were some other statistical variables on the sample? What was the skewness and the median rate of pass / geographic catchment area? Do you feel a four year window is large enough to measure trends? I am also curious about the homogeneity of data across districts or even the highest resolution point of analysis.

How are pass rates tied to planning and program development? Is education planning in the NR working under a goal oriented paradigm with respect to pass rates? I am curious what sort of marginal increases in “education” might be missed if we only focus on pass rates. But again – it goes back to what the goals of the program are.

On a final note, more out of curiosity than anything – what sort of statistical techniques are employed in your office?

Thanks Chris! Keep up the great work!

Patrick

PS

Similar to Mary, I found the constant switch between empiricism and opinion quite jarring. You made it sound like you have all the answers and I felt at times some of the data you were using wasn’t the focus of the article, but rather support for a pre-existing opinion, which in many ways isn’t any different from the approach taken by some of the organizations you’ve criticized.

I think I fixed the graphs, but now I’m having trouble excluding them from the gallery at the beginning. I’m working on that; WordPress is throwing me for a loop.

I will get to the important part of your comment, I promise! As a Ghanaian would say “I’m comin'”.

Thanks for the feedback, Patrick! I’m going to answer your questions one by one:

“Category mistake” is an excellent way of putting it. I think EWB’s role is to ask the tough questions of others and seek out responses. In this pursuit, I think EWB has big value-add in enabling transparency for organizations that take part in the kinds of activities I talked about. Is Free the Children’s model really unsustainable? Frankly, I don’t know. Their website isn’t descriptive or in-depth enough for me to tell. If I had more information about the model, then maybe I could make a value-free judgement. Without all of the information, though, I’m stuck with my (un-testable) assumptions.

You’re right; this kind of thing is not about to change (at least I don’t think it will). In fact, I think that the Ghanaian government has already done some leveraging of these kinds of projects. I mentioned that the majority of the 132 new schools were built by Ghana. NGOs built the remainder. What I think the Ghanaian government, at the District level in particular, needs to realize is that the supply of schools built by Westerners is not going to stop any time soon. There’s a sense of urgency around infrastructure projects, because it is assumed that they are in short supply. If the Ghanaian government can instead plan around these kinds of projects and figure out how to demand them, instead of just reporting about them, then I think schoolbuilding could definitely help Ghana. This requires coordination between the NGO and the government, though and I think it’s completely fair of me to criticize NGOs for doing that very, very poorly in the NR of Ghana.

For the purposes of this post, I ignored all nuances. Read my next one if you’re interested in finding out why. As I mentioned in my reply to Mary’s comment, I think that engaging well-to-do white people is, in fact, one benefit of this kind of project. I don’t know if that benefit outweighs the risks in every case, and I’m sure there are cases where it certainly does, like the one that you mentioned. I’m the last person to believe that blanket statements hold any relevance. That’s why I titled this one “So You Want to Build a School in Africa”, instead of “So You Want to Build a School in Ghana” or something. One of the points I was trying to make is that often Africa is seen as a blanket statement; all true, or all false. In fact, as you know, there’s plenty grey there to explore.

Sidenote to this question: if you go to the website of the build I referenced, you’ll find that their model claims to provide resources until the government is able to. The specifics of this methodology are not mentioned, so again it’s hard for me to make a value-free judgement. I find it interesting that it seems as though nobody who commented read about their model before doing so.

Biases abound in the data. My best answer to all of your questions about it are that this is all that the RESO has to work from and that I’m working on making their analyses as rigorous as they currently can be and setting up a process that facilitates more rigorous analyses. The current process for data involves aggregation at each level of government. As such, there’s very little breakdown into Districts or Schools at the Regional level. My hypothesis is that this is mainly due to the fact that data are only used for reporting and not really any analysis. I’m working with Alhassan now to produce a geographic distribution of scoring, access, enrolment, etc. because he sees the value in this. To be completely honest, the level of the rest of your questions about the data (skewness, median rate of pass, geographical catchment area, time span, homogeneity) is currently outside of the capacity of my office. These are all things to keep in mind, though, so thank you for keeping them at the front of my brain.

Pass rates are used for monitoring and evaluation of schools, an activity that is managed by the REO. Theoretically, when a school is low-performing, an inspection trip will be made to the school to figure out why. Then, the Director will have a discussion with the Headmaster to create some recommendations for improvement. Progress on recommendations is supposed to be monitored afterwards. I purposefully focussed my attention on the pass rate of a standardized test, because it demonstrates a really narrow scope of analysis. The BECE in particular is the exam which decides if a student will go on to SHS, so the pass rate is particularly interesting. If you don’t pass, then JHS3 is where your education finishes. The Ghanaian government just started a School Report Card (SRC) system which collects data about two other tests that are strictly designed to test comprehension. Unfortunately, there is only one year of SRC data as of now, so it’s not that useful yet. The bigger question that you’re getting at is “how do you measure learning?” The answer to this one is very, very, very complex and I think it only partly involves numbers in an Excel spreadsheet.

Currently, the RESO collects raw data from districts and calculates some UNESCO-suggested indicators (GER is one of them) based on census data. There is very little actual statistical analysis of the data. I hypothesize that this is for two reasons: 1. the population size is, and will remain, small (n = 20) and 2. simply put, they don’t know how to do it and there’s no incentive to learn, since reporting is the major use of data and reporting doesn’t require analyses outside of what is already done.

Thank you for the thoughtful comment, Patrick.

Well, I wholeheartedly loved your post, start to finish (except a few graphs wouldn’t load either). Upon reflection, it is maybe because I already had some notion that schoolbuilding wasn’t all it’s cracked up to be. And yes, the way that you consistently made strong statements could be offensive to those that have a strong emotional investment in the types of projects you were criticizing. However, I think some excuse can be made by the very fact that EWB has a strongly critical nature, and that you are used to people being able to look objectively at their own creations and their own hard work, and evaluate based on usefulness and not merely on effort invested or good intentions. It’s shocking, yes, to have someone openly criticize aid work, because “we’re all in it to make a better world”, but intentions are not sufficient!

In short, I think that being attached to any particular outcome makes negativity towards that outcome distracting, and doesn’t have anything to do with statistics (which is mostly what I was looking at, but on second read I didn’t find a lot of extra opinion, just satirical questions).

With that said, it is important to note that making generalisations from statistics is difficult. It’s hard to paint an entire scene with a broad brush, and potentially miss out on genuinely well-run projects such as the one that Patrick mentioned above. But how do we find these well-run setups when their marketing is misleading, perpetuating the idea that the physical structures are tantamount to good education, and enabling others to jump on the bandwagon of “good” aid?

Finally, I think the most troubling thing about the entire situation of independent aid projects (not just with school-builders) is the lack of connection with government activities. It seems to me that there is a ginormous prejudice against working with government at any level, whether in Canadian bureaucracy or ‘s inefficient and corrupt system. Carrying our notions of government inefficacy and supposed unsuitability over to another continent sometimes doesn’t make sense, and seems to be illustrated by your comments on the Ghanaian school system’s apparent ability to create and repair infrastructure. If projects cannot connect or operate effectively within a mediocre to good government, how will they help to contribute to a sustained system of education? Do school-building programs expect to indefinitely be the go-to to provide school buildings? Is there an unlimited supply in western people’s pocketbooks to contribute to this cause? Does the government get contact with independent schools at some future date, or are these schools forever out of the public system by virtue of their method of creation? How does government capacity improve if they have no stake in the outcome of these independent projects?

And NO, my strong opinion doesn’t mean that I think I have all the answers. That would be arrogant to the extreme. But I do think that I have learned enough to start the conversation, and share these thoughts loudly in hopes to get some intelligent dialogue started, where I can learn more and perhaps change or add nuance to my perspective. And yeah, it would be great to be constructive at every moment, but sometimes frustration boils over, and it seems this may be where Chris is coming from (correct me if I’m wrong), and at that point, patting people on the back for good intentions and upholding the status quo doesn’t seem quite good enough.

Thanks for the comment and feedback, Janine!

You make a good point that I’ve taken for granted the “EWB mindset” of being open to criticism and even seeking it out. It’s pretty easy to get stuck in that bubble when you’re immersed in people who share that mindset. I remember one occasion where I gave one of my professors some really critical feedback during a lecture. He wasn’t too happy and I was very confused, because I had just gotten back from an EWB conference, where critical feedback is highly valued. Lesson learned!

“In short, I think that being attached to any particular outcome makes negativity towards that outcome distracting, and doesn’t have anything to do with statistics.”

I love this statement; thank you for writing it. I think it’s one thing to be emotionally invested in work and whole other to be emotionally obsessed with your work. I’m always trying to be one step removed from my emotions when they influence my work because they create biases and potentially dangerous assumptions.

I like your point about the marketing machine employed by these organizations, too. How can you sift through all of these websites that say building a school = providing a better future in order to find one that makes the impact you want to see? One thing that I found with the small sample of websites I visited was a characteristic lack of transparency around their models. I mentioned in my reply to Patrick that I think this is where EWB’s value-add lies with respect to organizations of this type.

I was definitely channeling some frustration, but also some other things in writing this article. Read my next one if you want to find out why.

Graphs work for me now. Are school buildings made of textiles?

Good to know.

No, they aren’t. But if you go to the page of the build that I linked, you’ll find that they talk about how they carefully selected the textiles used in the school. To me, this is kind of a moot point. It’s a lot like choosing the kind of car you want to buy based on the colour, in that it ignores so many other more important things.

WHOA BESSIE. Attitude. I’m so glad this has finally been said. Actually though, I was hoping for maybe even more insight from your office. No exactly graphs, but perhaps what are other challenges that face the ministry that NGOs arent thinking about or are overlooking? Are there new challenges in education that you guys are talking about that are excluded even from development papers/literature/theorizing?

One big thing that is being completely overlooked by NGOs is teacher training and distribution. There are actually no NGOs in the NR working on distributing teachers or holding them accountable to their jobs. You’d be surprised at how much of a challenge both of these things are for the REO. Also, I’m comin’ with a full post about this soon.